Studying the Influence of Russian Chant on Stravinsky

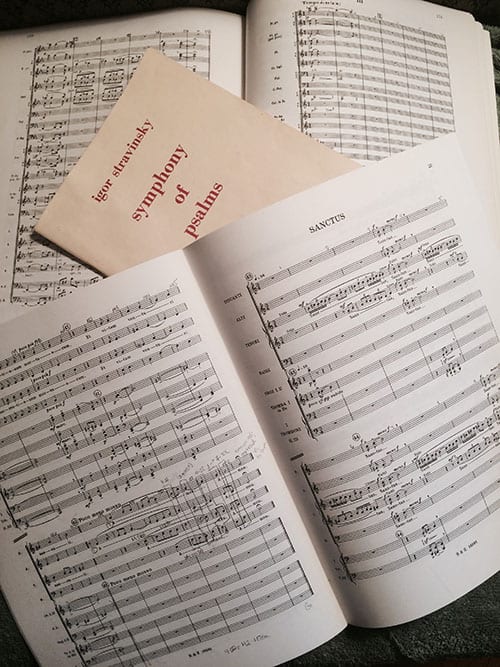

Two works comprising eight movements, 92 pages, and 785 measures. These compositions, Mass and Symphony of Psalms, are at the heart of what I’ve been working on for the past few weeks. Having received my scores from London, I made a preliminary sketch of the pieces, noting their overarching construction, marking cadences, and identifying the general forms used. I also studied the texts used in the works — where they come from, their purpose, and how often they have been set in the past. Basic sketches like this allow me to get a feel for the piece without getting too bogged down in chord function or voice leading — acting as an aural-big-picture, if you will.

Two works comprising eight movements, 92 pages, and 785 measures. These compositions, Mass and Symphony of Psalms, are at the heart of what I’ve been working on for the past few weeks. Having received my scores from London, I made a preliminary sketch of the pieces, noting their overarching construction, marking cadences, and identifying the general forms used. I also studied the texts used in the works — where they come from, their purpose, and how often they have been set in the past. Basic sketches like this allow me to get a feel for the piece without getting too bogged down in chord function or voice leading — acting as an aural-big-picture, if you will.

With a basic understanding of the pieces in mind, I traveled to the Irving S. Gilmore Music Library at Yale University, where I began to study the characteristics of early Russian polyphony and liturgical chant. This can be a difficult area of study because the neumatic system of notation used in the earliest transcriptions of Russian chant are still largely enigmatic to scholars. But fortunately, in 1772 the Holy Synod published a book of liturgical chants used by the Russian Orthodox Church in a modernized notational system, which gives us a glimpse of what the original chant notation may have indicated.

While at Yale, I studied some chant excerpts and listened to several recordings of monastery choirs performing liturgical chant. Much like Stravinsky, who was once quoted as having claimed to free music from the bar line, Russian liturgical chants are sung very freely — allowing the words and their meaning to take prominence over any sense of strong or weak beats. This same feeling is established in Stravinsky’s works, notably in the Gloria of Mass, where Stravinsky constantly changes the meter in which he is composing, while simultaneously utilizing sixteenth note triplets and quintuplets that break down the sense of rhythmic stability we generally associate with music.

Though by its nature this project is much more grounded in music theory than in musicology, I have also spent some time at Providence College’s own Phillips Memorial Library — studying Stravinsky himself and learning what he had to say about the composition of his Catholic liturgical works. Though he never specifically said he was looking back to Russian Liturgical Chant, Stravinsky did admit that he was composing these works with the intent of looking back into the past. We can also be certain that he did have exposure to early polyphonic chant, since he was not only a member of the Russian Orthodox Church himself, but also a student of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, who was instrumental in the resurgence of traditional Russian chant following a period of expansive Western influence. Additionally, Stravinsky was exposed to several examples of Georgian chant, which he studied and transcribed and which continued to fascinate him throughout his life.

Later this week, I will be continuing to delve into my research, traveling to Rochester, New York to visit the music library at the Eastman School of Music and to speak with a Russian hymnographer in Cooperstown, New York. I look forward to being able to flesh out my understanding of Russian chant and to use that knowledge to continue discovering the influence this tradition had on Stravinsky’s compositions.

Cheers,

Joan Miller