Understanding the beginnings of Russian chant

Sometimes, opportunities arise from the most unlikely occasions. When I applied for this grant back in February, I was visiting Ireland with the Providence College Liberal Arts Honors Program. One morning at the hotel — surrounded by books on choral masterworks and 20th century musicians and typing away furiously on an iPad Word document that I would eventually polish up into my grant application — I was approached by one of the theology professors who had accompanied us on the trip and who was curious as to what I was working on during vacation.

Sometimes, opportunities arise from the most unlikely occasions. When I applied for this grant back in February, I was visiting Ireland with the Providence College Liberal Arts Honors Program. One morning at the hotel — surrounded by books on choral masterworks and 20th century musicians and typing away furiously on an iPad Word document that I would eventually polish up into my grant application — I was approached by one of the theology professors who had accompanied us on the trip and who was curious as to what I was working on during vacation.

I explained the premises of my project to her and what I hoped to accomplish if I was awarded a grant. Before breakfast was over, she had told me she knew of a Russian hymnographer with whom I could get in touch if I received the grant. Grant-in-hand a few weeks later, I began reaching out to Mr. Nicholas Kotar — a fantasy author, Russian translator, musician, and hymnographer with a seemingly bottomless wealth of knowledge on Russian chant history and characteristics. Earlier this month, I had the pleasure of meeting Mr. Kotar while in upstate New York and speaking with him about my research.

We met in Cooperstown, a quaint little village about five hours southwest of Rochester, where I was conducting more research at the Sibley Library at the Eastman School of Music at the University of Rochester. Outside a local café and market, Mr. Kotar gave me a rundown of the history of Russian chant music — detailing for me when and how it developed. Unlike most other traditions, the Russian Orthodox liturgical practices stemmed solely from Russian folk music and the influences of the Byzantine church presence in the area. This is because the pagan religions, which dominated the area prior to Christianization, had no musical tradition of their own. This explains why some of the Russian chant music still sounds vaguely familiar to more Western ears — it is essentially Byzantine chant with a characteristically Russian spin on it.

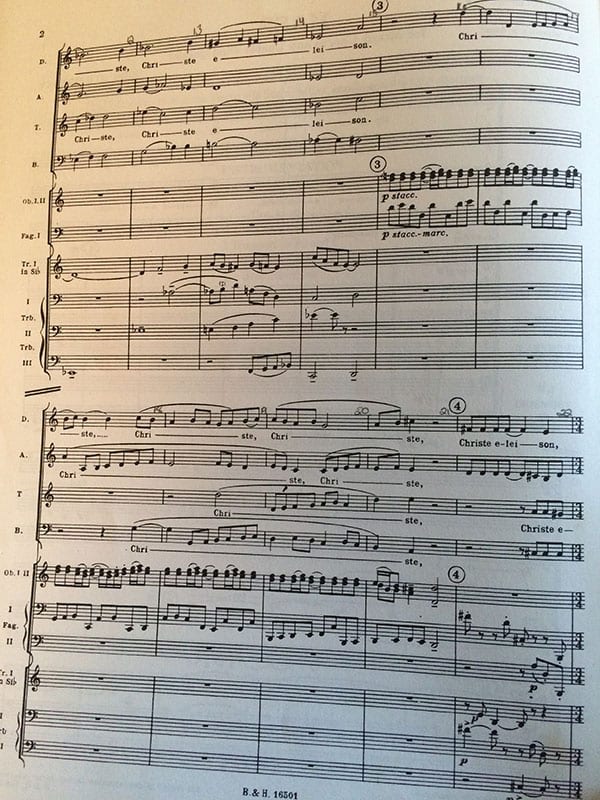

Znamenny chant, the first truly Russian liturgical music, developed soon after and is strikingly similar to Stravinsky’s works. Its characteristic elements include melismas (long lines sung on one syllable of text) and thetas (added syllables), both of which elongate important words in the chant. This focus on words would remain central to the compositional style of Russian chant, which always emphasized a conveyance of the text over melodic beauty. As such, sonorities that were unacceptable in the Roman Catholic liturgical tradition were allowed in the Russian canon, including open fourths and fifths, parallel seconds, and closed voicing with frequent voice crossing. When polyphony was introduced into the chant repertoire, Znamenny chant developed into Strochnoe chant, which translates to “line” or “horizontal” singing. This is an extremely appropriate descriptor, since these pieces involve a middle voice singing the original Znamenny chant surrounded by two outer voices that ornament the melody line but have no clear cut relation to it — creating a three-part piece in which each voice is independent. Similar tendencies can be seen in Stravinsky, especially in the interactions between his vocal and instrumental lines, which often are remarkably independent of each other. The included image is one such example. While the vocal lines in rehearsal three are clearly informed by each other, the accompanying instrumental line is largely independent of the vocal movement and either part could be easily taken out of the texture without destroying the other.

Supplied with these, and several other characteristics of Russian chant, thanks to the knowledge of Mr. Kotar, I have begun to create a spreadsheet analysis of the pieces — going through each measure with a fine tooth comb to look for patterns and characteristics that will be helpful in pinpointing how and when Stravinsky’s writing is influenced by Russian Orthodox chant.

The information I’m gathering ranges from the seemingly obvious, like what instruments are used and when, to the less conspicuous harmonic structure over the course of an entire movement or even the entire piece. Ultimately, this type of analysis will allow for the evaluation of Stravinsky’s composition in a way that will highlight the abundant similarities between Russian liturgical chant and the works of Stravinsky.

Cheers,

Joan