Emma Strempfer ’24

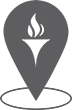

Reconsidering Dorothy Day: The Distinctly American Catholic

Emma Strempfer ’24, History and English major

Faculty Mentor: Dr. Jeffrey Johnson, History and Classics

Poster Presentation: Wednesday, April 24, 11 a.m. – 12:30 p.m.

Dorothy Day’s (1897-1980) life and work fell during a period of rapid social change in America. She lived as a bohemian radical and a self-proclaimed anarchist when she entered the political scene as a journalist for The Call, a newspaper affiliated with the Socialist Party of America. Disillusioned with hypocrisy and censorship on far-left socialist media, she explored and deepened her faith. Following conversion to Catholicism, Day founded the Catholic Worker. A faithful Catholic, Day criticized the Church. She recognized the failure of organized Christianity to effectively work against the misery that so many were facing. Instead of treating impoverished and immigrant New Yorkers as a faceless mass, she worked to publish stories on as many different individuals as possible, even sometimes for her story, living alongside them for weeks. Day gets tremendous attention from Christian writers and publishing houses and much less from secular academics. Writers like Jim Forrest, William Miller, and Terrence Wright praise Day’s virtue, her comfort with living a difficult life to help others, her kindness, her understanding, and her effortless balance of political radicalism and deep Catholic faith. To them, Day was sedate. Even for authors like Loughery and Randolph, who read her life through the most secular lens in 2021, her radicalism reads as a punchline, something silly in which she engaged in her early life before she became her true self when she grew to be an old, sage, Catholic mother. Day’s biographers tell the story of a young bohemian radical who, in the early 20th century, protested, was arrested, drank, slept around, had an abortion, and eventually turned to Christ in her early thirties beginning a life devoted to the poor and social justice in humble subservience to the Church. To gain a more robust understanding of Day’s life and work, historians must consider evidence that goes beyond a linear progression from radical bohemian to Catholic social activist.