Sean Gray ’21: A Revolutionary Summer: Researching Rhode Island in the Early 1770s

Tax evasion. Destruction of government property. Conspiracy. Rebellion and insurrection.

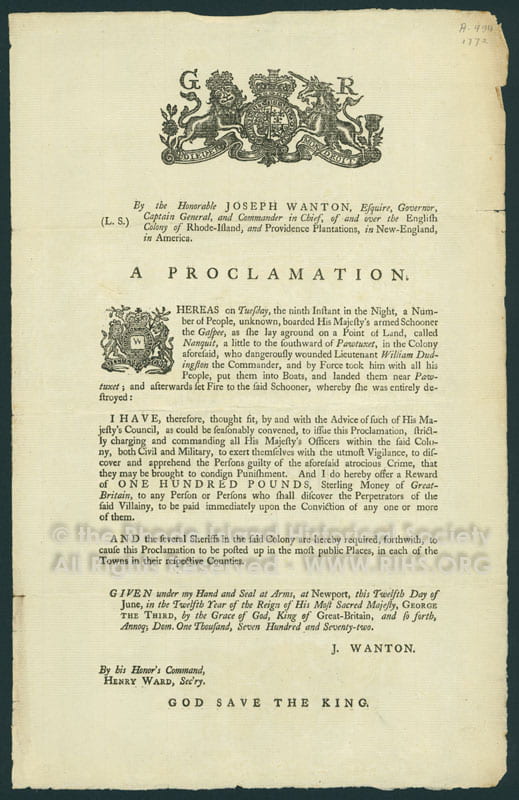

This might look like a dangerous criminal’s rap sheet, but it’s actually a brief summary of Rhode Island politics in the early 1770s. This summer, through a generous grant from the Center for Engaged Learning, I am conducting research about the colony’s last governor, Joseph Wanton, as he tried to keep the peace and protect the colony’s charter in the years before the American Revolution.

Wanton was not an American hero of any sort. He was a slaveholding merchant who only entered politics in the twilight of his life: at the age of seventy, he became governor because of infighting in the Rhode Island state legislature, and it was the only office he ever held. That same legislature removed him six years later on accusations of Toryism—being loyal to the British when independence seemed imminent. Nevertheless, the story of his time in power, often ignored by historians of the American Revolution, is an important one when considering the limits of imperial power, the causes of the American Revolution, and the history of Rhode Island.

The historiography—how historians write about events and people—around Wanton is limited. To my knowledge, no historian has put together a full-length biography of him, and few have written about his time as governor. But the ones that do write about him tend to dismiss him simply as a Tory without considering the sum total of his actions in office. My research, then, is centered around three questions: is it fair to call Wanton a Tory? How did the British empire and Rhode Islanders respond to his leadership as revolution began to grip Rhode Island? Above all else, why did Rhode Island ultimately depose Wanton and join the Revolution?

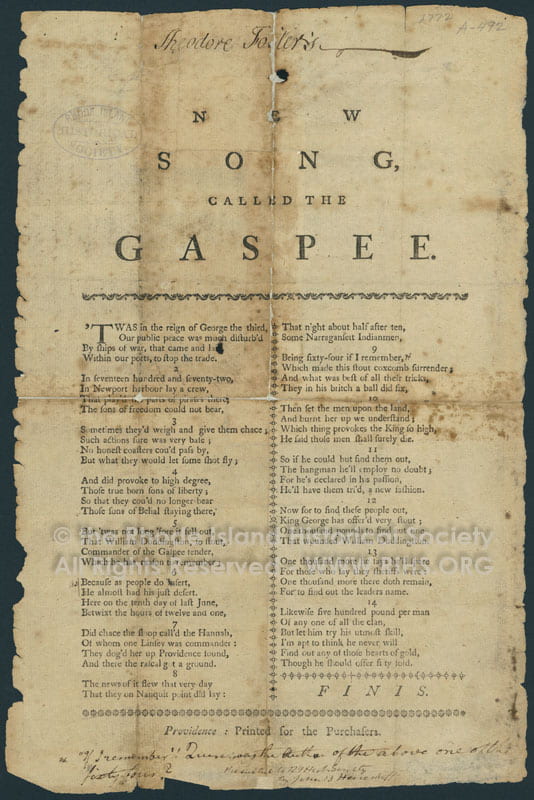

I’ve spent most of my summer reading newspapers, broadsides, and letters that discuss Wanton’s involvement in the attack on the HMS Gaspee, a British ship strictly enforcing trade laws that enraged Rhode Islanders. (The attack on the Gaspee and the year-long investigation that followed are the “destruction of government property” and “conspiracy” items on our RI rap sheet.)

Along with this post, I’ve attached two important documents—a proclamation issued days after the attack and a broadside poem that circulated simultaneously. Items like these are central to my research—they demonstrate competing perspectives of the same event. Take a look at them yourself and see what you can figure out about how Rhode Islanders might have understood the attack on the Gaspee. Who might have written these pieces? What language does each use to describe the attack? Do the authors see the attack as a good or bad thing? Why? I use this questioning process constantly as I read documents to craft a narrative about Wanton and Rhode Island in the 1770s.

This research will ultimately culminate in my honors senior thesis—an original research paper more than fifty pages in length and my first extended contribution to the discipline of history. My working title is “The Ordeal of Joseph Wanton: Power, Protest, and the People in Revolutionary-Era Rhode Island.” Thank you to Dr. Steve Smith, of the Department of History and Classics, for your support and guidance, to the Rhode Island Historical Society, for access and use of items from your NETOP database and other expansive collections, and to the Center of Engaged Learning, for your generosity and continued support of student scholarship and creativity.